Mudrat

Member

Round-trip distance/elevation gain/duration: 10.75 miles / 3,900 feet/ 11.5 hours (8:00 a.m. – 7:30 p.m.)

Conditions: 24” sugar snow on bushwhack/ice, rock, semi consolidated snow on ascent/packed trails.

Partners: NP & Richard Cartier

Photos ~ Video

It’s difficult to describe why I love this slide (perhaps love-hate is a better term). It’s the prize of Upper Wolfjaw Mt. and one of the most difficult Adirondack slides. The combination of setting, challenge and general character set it apart from most others in my mind. While there is plenty of clean rough slab, during non-snow/ice seasons, it harbors moss in the most precarious places, most notably, on the crux of the climb—part of the draw for me. Oddly, this is also the same reason that I sometimes dislike the slide. In any case, climbing it requires total emersion in the moment. This alone draws me back to it over and again.

My first visit was with Neil Luckhurst in 2011, then NP in 2012. NP commented that he’d likely never come back to it as an unprotected climb…that it was too dangerous due to the exposure and moss that blankets the dihedral. A slip would send you tumbling 325 feet down to the base and into the debris. A winter ascent was another story, however—if it setup with the proper combination of ice and consolidated snow. We missed the window last year so it fell to our winter 2014 priority list.

Together with NP’s long-time friend, Richard (3 weeks back from Aconcagua in Argentina), we set out to survey the conditions and, hopefully, climb it via an exciting line. With temperatures in the 20’s, it was perfect weather. By the time we were on the Lake Road, I knew we might also capture some spectacular photograph…crisp blue skies and low humidity.

Beaver Meadow Falls was fat with ice and the trail beyond was well packed. We began the mile-long bushwhack a few hundred feet after passing onto state land by intersecting the drainage just to the right. Unconsolidated knee-deep snow made me groan inside; I didn’t want another repeat of the Santanoni Mt. bushwhack from a couple weeks ago. Soon after, we happened upon a snow-boarder’s track and enjoyed the respite from trail-breaking. It was short-lived and ended at the next confluence of slide tracks at 2,600 feet in elevation (following the slide track left leads back to the Beaver Meadow Trail while right leads to the 2011 slide on Upper Wolfjaw).

The White and Sabretooth slides drain into the primary stream from the northwest (right) at 2,700 feet in elevation about 1/10 of a mile beyond the confluence. A room sized boulder and tangle of debris hides the small drainage stream. Once in the stream bed, the highlights include a beautifully layered ledge on the left and open slab about 2/3 of the way to the White Slide. Following the drainage off the slab to the right leads to the base of the Sabretooths while diverting left leads more toward the White Slide. In hindsight, I believe it’s easier to follow the Sabretooth Slide approach to the base of the western-most slide (there are tracks) and then cut left over to the White’s base which lies less than 100 feet of elevation gain higher.

This day we bushwhacked directly toward our target through the woods. Switching leads, with Richard doing much of the trail-breaking, we made our way slowly upward. The tightly knit forest loosened as we neared the slide base. I watched our progress by measuring it against the Sabretooths through the forest.

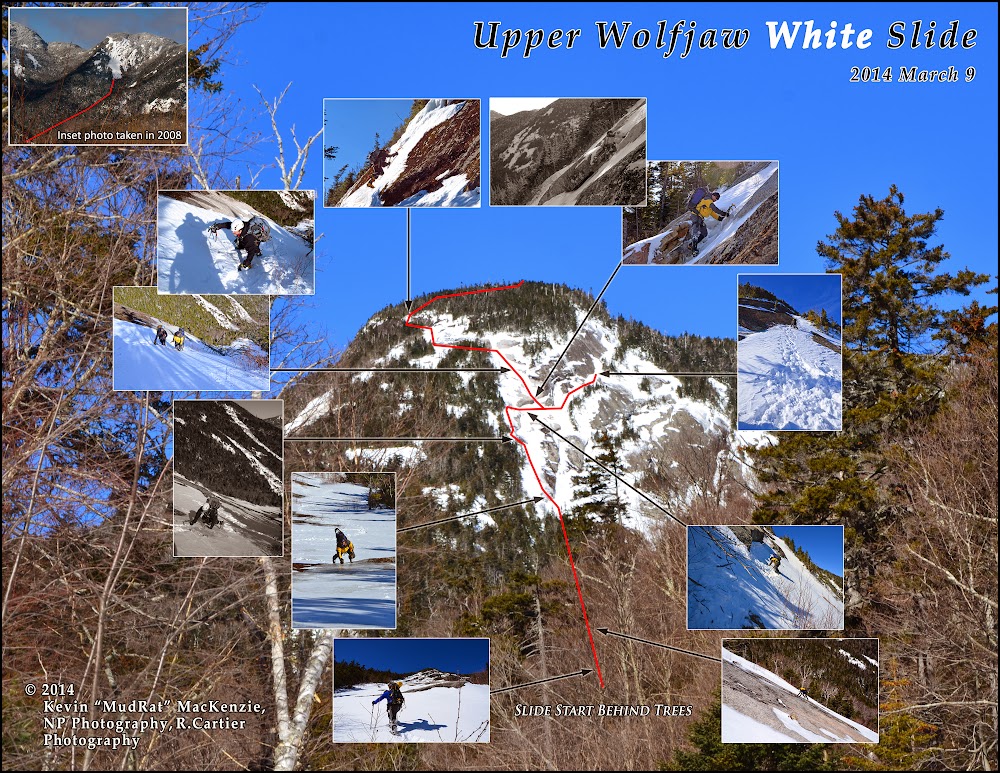

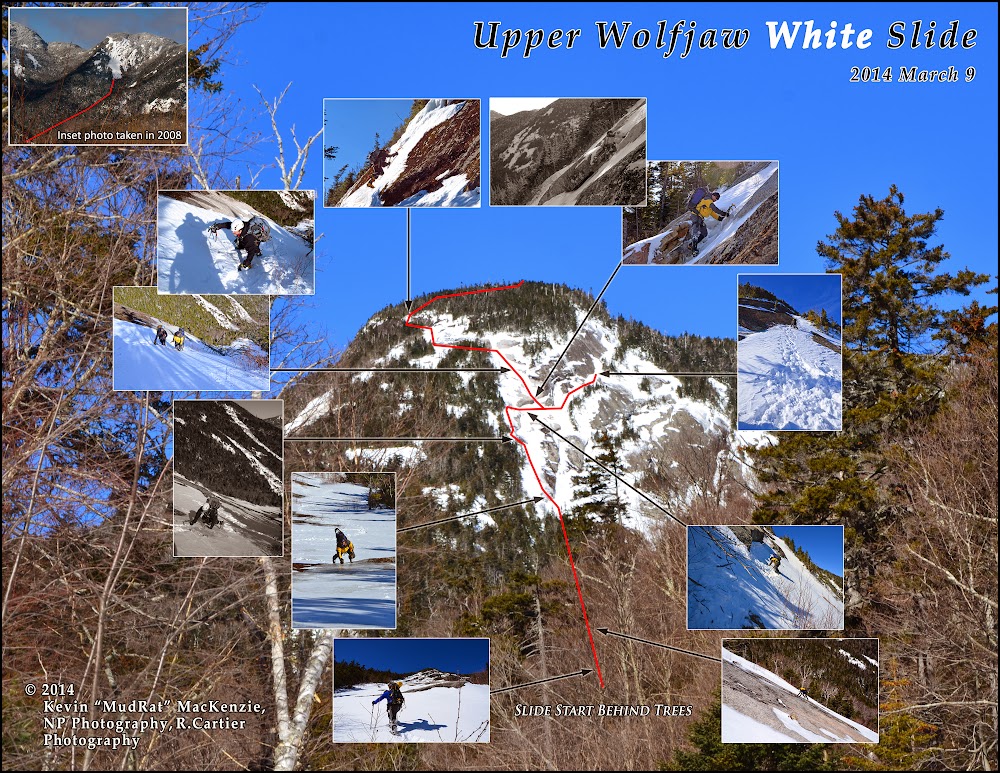

We arrived at 12:30 p.m. and set about the business of changing from snowshoes to crampons and studying the route. NP came up with an interesting variation off a direct climb up the slide. We’d try to traverse to the right after about 400 feet of elevation gain, above the crux (the right-leaning dihedral in the center). There were three obvious choices that might get us to the traverse. Each had a long runout and with unique qualities from one another. They included:

• A line up the left-hand side via several snowfields and some intermittent ice. This required a total traverse across the slide track, the best spot to be determined as we approached.

• A line up the summer crux described above. This seemed to have a little snow attached and assumed the most risk.

• A line up through deeper snow on the right where the White Slide borders the old-exposure slab. This looked like the least exposed, most cumbersome and least exciting option.

From the bottom, the slide appears very benign--almost easy and lower than 600 feet. The steep exposed slab sections above appear rather flat from below. After about 200 feet of elevation gain it is obvious that this is one of the more serious Adirondack slide climbs. Higher and it crosses the threshold into low fifth-class climbing with an extensive runout should one fall. By then you’re quite committed.

Bottom of the slide. Things look relatively low-key above from this perspective.

Ascent

The knee-deep snow quickly thinned as we climbed onto a bulge in the slide; some portions were exposed while some had verglas. Richard followed a consistent line of the ½ glaze while NP and I climbed a little to the left along the first route described above. A snowfield a couple hundred feet higher gave us a feel for the conditions—mixed. Crampons bit into ice, scraped on underlying rock and sank into deeper areas of crust and snow as we worked our way up to another section of thin ice. Gentle swings from the wrist gave me just enough penetration to belay myself without striking (and dulling) the tip on the stone just below. The first stick, a hollow thud, spider-webbed a portion of the ice that had delaminated. The ice was, however, attached just above so we felt it was safe to continue.

While on an adjacent snowfield, we watched Richard delicately climb along the central dihedral-his skill was obvious. He had only a bit of snow underfoot along the corner (on the northern side of it). Whether there was ice or just rock underneath, I don’t know. He explored about 2/3 of the way up, but eventually down-climbed to follow our line.

Above, Richard on the low-angle slab following the thin line of ice...all finesse.~~Below, Richard partway up the summer crux.

NP on the right-hand line.

We were forced (or wisely chose) to stay close to the edge for the next 100 feet since the ice seemed to be delaminating just to the right. The position felt far too exposed to take the chance just for the sake of climbing on ice—there’d be more opportunities for that above. NP led the way and found a nice spot above the summer crux to traverse across the slide. As a point of reference, in summer the underlying stone is browner and more contoured than the rest of the slide.

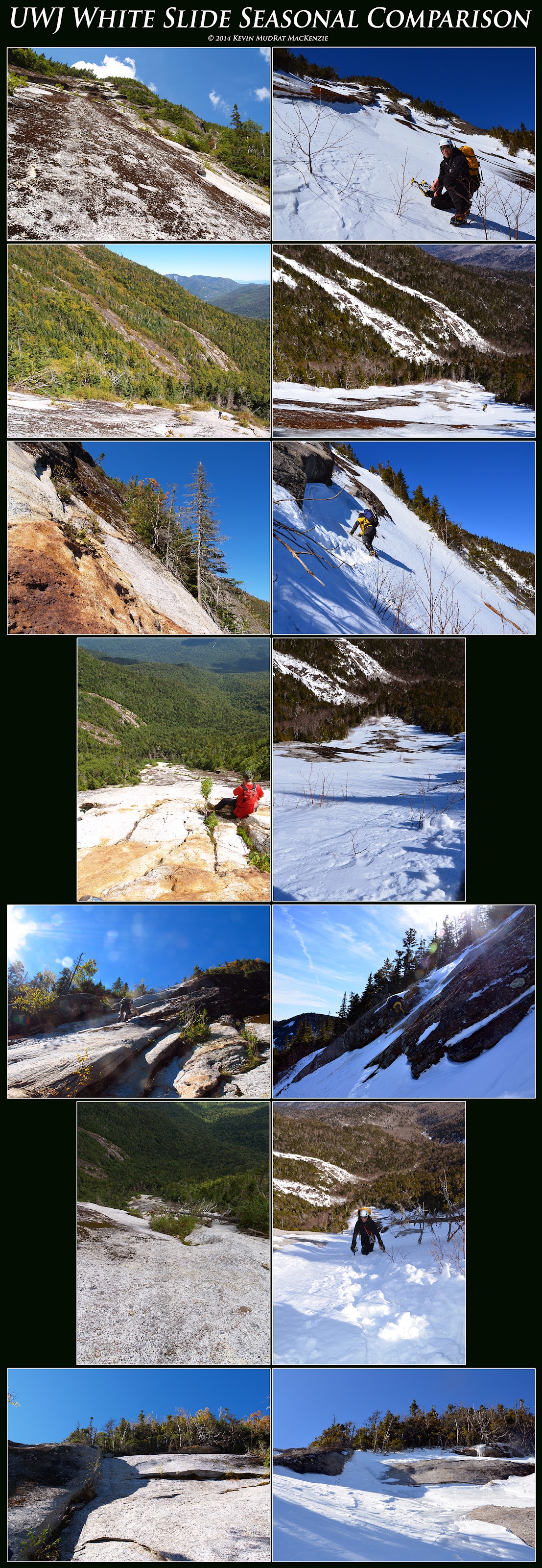

View across the slide traverse. See 'Seasonal Comparison' in photo for NP on the traverse an idea of the pitch.

View down from the crux.

With a large overlap above and snowfield underfoot, I followed a trench carved by NP’s passage. Meanwhile, he stood on the other side videoing the events at hand. I found the challenge was determining what was underfoot. With one step I would plunge shin deep; the next I’d find ice under a few inches of snow. The view down the 45 degree exposure and off to the east was dominated by the Sabretooth Slides, Giant in the distance and the Green Mts. on the horizon. It was simply stunning against the cobalt blue sky.

Conditions: 24” sugar snow on bushwhack/ice, rock, semi consolidated snow on ascent/packed trails.

Partners: NP & Richard Cartier

Photos ~ Video

It’s difficult to describe why I love this slide (perhaps love-hate is a better term). It’s the prize of Upper Wolfjaw Mt. and one of the most difficult Adirondack slides. The combination of setting, challenge and general character set it apart from most others in my mind. While there is plenty of clean rough slab, during non-snow/ice seasons, it harbors moss in the most precarious places, most notably, on the crux of the climb—part of the draw for me. Oddly, this is also the same reason that I sometimes dislike the slide. In any case, climbing it requires total emersion in the moment. This alone draws me back to it over and again.

My first visit was with Neil Luckhurst in 2011, then NP in 2012. NP commented that he’d likely never come back to it as an unprotected climb…that it was too dangerous due to the exposure and moss that blankets the dihedral. A slip would send you tumbling 325 feet down to the base and into the debris. A winter ascent was another story, however—if it setup with the proper combination of ice and consolidated snow. We missed the window last year so it fell to our winter 2014 priority list.

Together with NP’s long-time friend, Richard (3 weeks back from Aconcagua in Argentina), we set out to survey the conditions and, hopefully, climb it via an exciting line. With temperatures in the 20’s, it was perfect weather. By the time we were on the Lake Road, I knew we might also capture some spectacular photograph…crisp blue skies and low humidity.

Beaver Meadow Falls was fat with ice and the trail beyond was well packed. We began the mile-long bushwhack a few hundred feet after passing onto state land by intersecting the drainage just to the right. Unconsolidated knee-deep snow made me groan inside; I didn’t want another repeat of the Santanoni Mt. bushwhack from a couple weeks ago. Soon after, we happened upon a snow-boarder’s track and enjoyed the respite from trail-breaking. It was short-lived and ended at the next confluence of slide tracks at 2,600 feet in elevation (following the slide track left leads back to the Beaver Meadow Trail while right leads to the 2011 slide on Upper Wolfjaw).

The White and Sabretooth slides drain into the primary stream from the northwest (right) at 2,700 feet in elevation about 1/10 of a mile beyond the confluence. A room sized boulder and tangle of debris hides the small drainage stream. Once in the stream bed, the highlights include a beautifully layered ledge on the left and open slab about 2/3 of the way to the White Slide. Following the drainage off the slab to the right leads to the base of the Sabretooths while diverting left leads more toward the White Slide. In hindsight, I believe it’s easier to follow the Sabretooth Slide approach to the base of the western-most slide (there are tracks) and then cut left over to the White’s base which lies less than 100 feet of elevation gain higher.

This day we bushwhacked directly toward our target through the woods. Switching leads, with Richard doing much of the trail-breaking, we made our way slowly upward. The tightly knit forest loosened as we neared the slide base. I watched our progress by measuring it against the Sabretooths through the forest.

We arrived at 12:30 p.m. and set about the business of changing from snowshoes to crampons and studying the route. NP came up with an interesting variation off a direct climb up the slide. We’d try to traverse to the right after about 400 feet of elevation gain, above the crux (the right-leaning dihedral in the center). There were three obvious choices that might get us to the traverse. Each had a long runout and with unique qualities from one another. They included:

• A line up the left-hand side via several snowfields and some intermittent ice. This required a total traverse across the slide track, the best spot to be determined as we approached.

• A line up the summer crux described above. This seemed to have a little snow attached and assumed the most risk.

• A line up through deeper snow on the right where the White Slide borders the old-exposure slab. This looked like the least exposed, most cumbersome and least exciting option.

From the bottom, the slide appears very benign--almost easy and lower than 600 feet. The steep exposed slab sections above appear rather flat from below. After about 200 feet of elevation gain it is obvious that this is one of the more serious Adirondack slide climbs. Higher and it crosses the threshold into low fifth-class climbing with an extensive runout should one fall. By then you’re quite committed.

Bottom of the slide. Things look relatively low-key above from this perspective.

Ascent

The knee-deep snow quickly thinned as we climbed onto a bulge in the slide; some portions were exposed while some had verglas. Richard followed a consistent line of the ½ glaze while NP and I climbed a little to the left along the first route described above. A snowfield a couple hundred feet higher gave us a feel for the conditions—mixed. Crampons bit into ice, scraped on underlying rock and sank into deeper areas of crust and snow as we worked our way up to another section of thin ice. Gentle swings from the wrist gave me just enough penetration to belay myself without striking (and dulling) the tip on the stone just below. The first stick, a hollow thud, spider-webbed a portion of the ice that had delaminated. The ice was, however, attached just above so we felt it was safe to continue.

While on an adjacent snowfield, we watched Richard delicately climb along the central dihedral-his skill was obvious. He had only a bit of snow underfoot along the corner (on the northern side of it). Whether there was ice or just rock underneath, I don’t know. He explored about 2/3 of the way up, but eventually down-climbed to follow our line.

Above, Richard on the low-angle slab following the thin line of ice...all finesse.~~Below, Richard partway up the summer crux.

NP on the right-hand line.

We were forced (or wisely chose) to stay close to the edge for the next 100 feet since the ice seemed to be delaminating just to the right. The position felt far too exposed to take the chance just for the sake of climbing on ice—there’d be more opportunities for that above. NP led the way and found a nice spot above the summer crux to traverse across the slide. As a point of reference, in summer the underlying stone is browner and more contoured than the rest of the slide.

View across the slide traverse. See 'Seasonal Comparison' in photo for NP on the traverse an idea of the pitch.

View down from the crux.

With a large overlap above and snowfield underfoot, I followed a trench carved by NP’s passage. Meanwhile, he stood on the other side videoing the events at hand. I found the challenge was determining what was underfoot. With one step I would plunge shin deep; the next I’d find ice under a few inches of snow. The view down the 45 degree exposure and off to the east was dominated by the Sabretooth Slides, Giant in the distance and the Green Mts. on the horizon. It was simply stunning against the cobalt blue sky.

Last edited: